I wanted to write a follow-up post to my piece on the "Four Types of Donors." For a refresher, here's the matrix I used to divide up the donor market into four quadrants (for more information on this, see the original post):

The type of donors organizations want are in the top right quadrant: Donors with a high interest in whatever the organization is working on, as well as a high capacity to give. Organizations have many options to mobilize their donors into the top-right corner of this matrix. I discussed the movement upwards in my previous post on this topic--that is, making it easier for donors to give their resources through simplified ways of giving, like texting donations or social networking sites. (Of course, another way to do this would be to increase donors' overall resources, which is a lot harder to do and probably not the goal of most fundraisers.) But what I didn't really touch on was how to move donors to the right--that is, make them more interested in what an organization is doing.

To do this, I think non-profits need to have a broader communications strategy, focused on increasing awareness and engagement in their issues. Which is much easier said than done. When thinking about non-profit advocacy, I always come back to the marketing adage: "I know that half our marketing is working, I'm just not sure which half." It's hard, if not impossible, to tell if information being put out there is increasing engagement or donations and what is wasted on deaf ears. With limited resources, it makes sense most non-profits don't devote a lot of time to raising awareness in the broader public. Philanthropy Action did a study a while ago about the ineffectiveness of social media on leveraging support for non-profits, which I think shows the difficulty of using engagement techniques to increase support--i.e., moving donors from the left of the matrix to the right.

However, the original reason I created this matrix was to discuss my issues with "slacktivism"--the notion that we can do good without doing a lot. The most concrete and (unfortunately) prevalent example of slacktivism is embedded philanthropy, like the RED campaign, where people make a consumption purchase that has a small donation to a specific organization tied into that purchase.

This is only one of many examples of corporations partnering with non-profits to help increase support. I think it's these partnerships that have the most potential to increase engagement. Instead of a simple donation, why not include some information about child labor in the garment industry along with that GAP t-shirt? When Apple starts marketing their next generation of I-Pads, why not create an advertising campaign about the use of conflict materials in common electronics? These types of campaigns could have a much larger impact on what non-profits are working for than any amount of increased monetary giving. Corporations with the expendable resources to get behind these initiatives could start a new wave of corporate responsibility not just centered around dollar donations. This could really get people moving into that ideal top-right corner of the donor matrix.

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Sunday, June 20, 2010

Pledgers need to not just give smart, but be engaged

While it was overshadowed by the unveiling of the Buffett/Gates Giving Pledge,* another significant announcement was made this week in the world of philanthropy, back in my home town of Minneapolis: Winston Wallin received the first "Minnesota Engaged Philanthropist" award from the Twin-Cities based Social Venture Partners.

This announcement has personal significance for me--I was one of Wallin's "Wallin Scholars," a program that has given over $20 million in college scholarships to help people like me afford tuition. But the award's importance also resonates beyond Twin Cities youth and serves as a message for the average billionaire joining the Gates/Buffett entourage. Giving is simply no longer enough, but now it has to be smart and engaged.

Adding another dimension to the "smart giving" mantra, the concept of engaged philanthropy (which had its third annual conference in Minneapolis last week) pushes philanthropists to not only give and not only give smart, but be involved in the supporting organization's work. In the case of Wallin, he fundraised to build a new cancer center at the University of Minnesota and then came on--at no pay--to turn around the floundering health sciences division. He also has met every one of his Scholars--there are around 3,000 of us now. (He's a very nice man, with a very nice family.)

For me, engaged philanthropy is about doing whatever the philanthropist can do to support the organization's mission with the skills and resources he or she has. This could be technical assistance, fundraising, helping with staff hiring, in-kind donations, whatever. Being engaged means finding those needs in the organization or in the community and then filling them.

In an op-ed piece at the Chronicle of Philanthropy, Susan Wolf Ditkoff and Thomas J. Tierney said that those philanthropists willing to sign on to the Giving Pledge and donate half their fortune to charity can't just jump into "check-writing mode," but need to direct their resources to programs that work. I would take that a step further and say that these philanthropist need to get into the thick of it to figure out what programs work and how they can offer the full extent of their resources to the organizations they support. Like the Wallins and the McCary family--who funded my scholarship from the Wallin Foundation and sent me cards and Christmas presents to keep in touch--those new Pledgers need to not only give smart, but be engaged.

The flip side of this increased engagement--which was brought up in the Star Tribune article linked above--is a donor who takes too much control over an organization. I can see this being a problem in certain cases, but a continued focus from both the donor and the organization on its mission can help mitigate those issues and guide an organization's actions. And, considering the lack of interest most donors have for impacts, an increased awareness and involvement in an organization can never be a bad thing.

*For more information on the Giving Pledge see the Chronicle of Philanthropy coverage, Tactical Philanthropy's analysis and the strangely Skull-and-Bones-esque back story on Fortune.

This announcement has personal significance for me--I was one of Wallin's "Wallin Scholars," a program that has given over $20 million in college scholarships to help people like me afford tuition. But the award's importance also resonates beyond Twin Cities youth and serves as a message for the average billionaire joining the Gates/Buffett entourage. Giving is simply no longer enough, but now it has to be smart and engaged.

Adding another dimension to the "smart giving" mantra, the concept of engaged philanthropy (which had its third annual conference in Minneapolis last week) pushes philanthropists to not only give and not only give smart, but be involved in the supporting organization's work. In the case of Wallin, he fundraised to build a new cancer center at the University of Minnesota and then came on--at no pay--to turn around the floundering health sciences division. He also has met every one of his Scholars--there are around 3,000 of us now. (He's a very nice man, with a very nice family.)

For me, engaged philanthropy is about doing whatever the philanthropist can do to support the organization's mission with the skills and resources he or she has. This could be technical assistance, fundraising, helping with staff hiring, in-kind donations, whatever. Being engaged means finding those needs in the organization or in the community and then filling them.

In an op-ed piece at the Chronicle of Philanthropy, Susan Wolf Ditkoff and Thomas J. Tierney said that those philanthropists willing to sign on to the Giving Pledge and donate half their fortune to charity can't just jump into "check-writing mode," but need to direct their resources to programs that work. I would take that a step further and say that these philanthropist need to get into the thick of it to figure out what programs work and how they can offer the full extent of their resources to the organizations they support. Like the Wallins and the McCary family--who funded my scholarship from the Wallin Foundation and sent me cards and Christmas presents to keep in touch--those new Pledgers need to not only give smart, but be engaged.

The flip side of this increased engagement--which was brought up in the Star Tribune article linked above--is a donor who takes too much control over an organization. I can see this being a problem in certain cases, but a continued focus from both the donor and the organization on its mission can help mitigate those issues and guide an organization's actions. And, considering the lack of interest most donors have for impacts, an increased awareness and involvement in an organization can never be a bad thing.

*For more information on the Giving Pledge see the Chronicle of Philanthropy coverage, Tactical Philanthropy's analysis and the strangely Skull-and-Bones-esque back story on Fortune.

Sunday, June 13, 2010

Four Types of Donors

I've written a lot about my feelings on the rise of "slacktivism"--that is, the growing prevalence and acceptance of all the small, simple, easy things people can do to make a difference: Embedded philanthropy, tweeting for donations, virtual volunteering, signing petitions, running races, etc. When I saw this new list of "5 Cool Things You Can Do RIGHT NOW To Make a Difference" (OMG!) I thought I'd fire off another snarky post lambasting this degradation of the philanthropic community. But then I remembered this satirical post a friend had passed on to me on the BP Oil Spill and I realized I couldn't really out do that (it's hilarious). Instead, I decided to do something a little more productive.

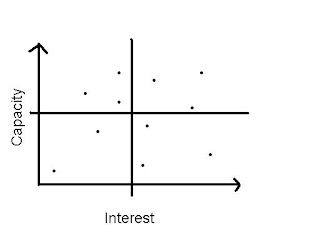

My main issue with slackivism and the products/services that cater to the slacktivist model is the level of complacency (I think) they breed in people. I recognize that we all have varying degrees of interest in a cause and varying degrees of resources, but I also do not accept that those varying levels can't be pushed to get more out of people. To help illustrate this, I created this graph:

(Sorry for the kindergarten image quality.)

On the x axis, we have an individual's level of interest, be it in a cause, specific field or in social change in general. For the purposes of this discussion, let's be general and assume we're talking about a person's interest in social change. On the y axis, we have a person's capacity to devote resources to that cause--in our case, social change. The dots on the graph represent individuals. We can see that someone can have a high interest in social change, but not a lot of resources (time, money) to devote to "the cause," while there can also be someone with a high capacity to donate to "the cause" but not a lot of interest to do so. And there also is every variation of people between the two.

(Before going further explaining this model, I think it's important to note that I conceptualize these individuals represented on the graph as being in a singularity prior to the act of donation--that is, they have not yet given, but could do so in the future. These two axes represent an interest and a capacity that can be captured by non-profits, social change organizations, or what have you, at any point in the future. Moving on.)

To make things simpler, I decided to divide up the graph into segments:

Now, again, this is a simplification for the purposes of the model. Obviously, people don't just have either "high" or "low" interest in social change, or "high" or "low" capacity to give. But, this simplification helps us talk about the different characteristics. (Another note: I think it's safe to ignore the individuals who fall directly on either axes of the graphs; either people with no capacity to give whatsoever or those with absolutely no interest. Neither of those groups concern us in this model.)

In Q1, we have people with a high capacity to give, but a low interest. These are wealthier, privileged people with access to resources that make it easy to give, but, for whatever reason, don't want to. In Q2, we have people with a high capacity to give and a high interest. These are privileged donors with a strong desire to give. In Q3, we have people with a low capacity to give as well as a low interest. In Q4, we have people with a low capacity to give, but a high interest. In this quadrant, people are willing to give and be more engaged, but don't have the resources to do so.

Now that these markets are segmented, we can see the effect of the slackivist methods of giving on each of them. I will start with the easy ones. For Q2, the methods will have little to no effect. These donors are already highly engaged and contributing greatly. They do not need anything to help them give. For Q3, these donors don't have much to give and not a lot of interest to do so. If they use the slacktivist methods, it will be only slightly.

But the methods will have a large impact on Q4. For a Q4 donor without a lot of time or resources to be engaged, but a strong desire to make a difference, the "slacktivism" technologies actually make it easier for these donors to be a part of the philanthropic market. Their capacity to give is increased by the easier accessibility and increased connectivity of slacktivist modes of giving, which "mobilizes" them from their position in Q4 to a position in Q2. Woo! Alright!

So, the Q1 area is where I come up against my issues with slacktivism. For these people with low levels of interest, but high resources, slacktivism becomes a stopping point. Instead of feeding more information and aiming for increased engagement, the slacktivist methods instead simply extract increased-frequency, but still small donations from this quadrant. A raising of awareness could mobilize people from Q1 to Q2--which would lead to higher engagement and contributions--but instead, the Q1 donors remain stationary.

Now, you might ask, what's the big deal? Q1 people are giving more than they would have, as are the Q4 donors, so what's the problem?

Well, I would answer, it matters precisely because the slacktivism methods are not mobilizing Q1 people into Q2. There are huge amounts of time, resources and energy to be gained from the Q1 market share (especially in the Western world) and slacktivism is holding those people back. While it may mobilize the Q4 donors, the market share of Q1 (again, especially in the Western world) is much, much higher than the market share of Q4. There is so much to be gained from these potential donors, but slacktivism allows them to remain on the left side of the matrix.

Given a choice between buying a coffee bag that comes with a contribution to the Global Fund and one that does not, it's obviously better to choose the one that does. But accepting this as the only choice out there to potential donors is a huge misrepresentation of the possibilities of the philanthropic market and the world of social change. Things that mobilize the donors from Q1 to Q2 is where we need to be focusing our energies, not on making t-shirts with charitable donations woven into them.

That is my issue with slacktivism, embedded giving, texting donations, tweeting for charities, whatever you want to call it. People (especially in this country) can and should be doing more to be a part of social change.

(I recognize this was a lot. I appreciate you reading it all the way through. If you have any questions or thoughts on my model, my matrix, my subsequent analysis of it or anything, I'd love to hear from you through email or in the comments.)

My main issue with slackivism and the products/services that cater to the slacktivist model is the level of complacency (I think) they breed in people. I recognize that we all have varying degrees of interest in a cause and varying degrees of resources, but I also do not accept that those varying levels can't be pushed to get more out of people. To help illustrate this, I created this graph:

(Sorry for the kindergarten image quality.)

On the x axis, we have an individual's level of interest, be it in a cause, specific field or in social change in general. For the purposes of this discussion, let's be general and assume we're talking about a person's interest in social change. On the y axis, we have a person's capacity to devote resources to that cause--in our case, social change. The dots on the graph represent individuals. We can see that someone can have a high interest in social change, but not a lot of resources (time, money) to devote to "the cause," while there can also be someone with a high capacity to donate to "the cause" but not a lot of interest to do so. And there also is every variation of people between the two.

(Before going further explaining this model, I think it's important to note that I conceptualize these individuals represented on the graph as being in a singularity prior to the act of donation--that is, they have not yet given, but could do so in the future. These two axes represent an interest and a capacity that can be captured by non-profits, social change organizations, or what have you, at any point in the future. Moving on.)

To make things simpler, I decided to divide up the graph into segments:

which quarters off the plane and allows us to nicely divide up the donor market into this matrix:

Now, again, this is a simplification for the purposes of the model. Obviously, people don't just have either "high" or "low" interest in social change, or "high" or "low" capacity to give. But, this simplification helps us talk about the different characteristics. (Another note: I think it's safe to ignore the individuals who fall directly on either axes of the graphs; either people with no capacity to give whatsoever or those with absolutely no interest. Neither of those groups concern us in this model.)

In Q1, we have people with a high capacity to give, but a low interest. These are wealthier, privileged people with access to resources that make it easy to give, but, for whatever reason, don't want to. In Q2, we have people with a high capacity to give and a high interest. These are privileged donors with a strong desire to give. In Q3, we have people with a low capacity to give as well as a low interest. In Q4, we have people with a low capacity to give, but a high interest. In this quadrant, people are willing to give and be more engaged, but don't have the resources to do so.

Now that these markets are segmented, we can see the effect of the slackivist methods of giving on each of them. I will start with the easy ones. For Q2, the methods will have little to no effect. These donors are already highly engaged and contributing greatly. They do not need anything to help them give. For Q3, these donors don't have much to give and not a lot of interest to do so. If they use the slacktivist methods, it will be only slightly.

But the methods will have a large impact on Q4. For a Q4 donor without a lot of time or resources to be engaged, but a strong desire to make a difference, the "slacktivism" technologies actually make it easier for these donors to be a part of the philanthropic market. Their capacity to give is increased by the easier accessibility and increased connectivity of slacktivist modes of giving, which "mobilizes" them from their position in Q4 to a position in Q2. Woo! Alright!

So, the Q1 area is where I come up against my issues with slacktivism. For these people with low levels of interest, but high resources, slacktivism becomes a stopping point. Instead of feeding more information and aiming for increased engagement, the slacktivist methods instead simply extract increased-frequency, but still small donations from this quadrant. A raising of awareness could mobilize people from Q1 to Q2--which would lead to higher engagement and contributions--but instead, the Q1 donors remain stationary.

Now, you might ask, what's the big deal? Q1 people are giving more than they would have, as are the Q4 donors, so what's the problem?

Well, I would answer, it matters precisely because the slacktivism methods are not mobilizing Q1 people into Q2. There are huge amounts of time, resources and energy to be gained from the Q1 market share (especially in the Western world) and slacktivism is holding those people back. While it may mobilize the Q4 donors, the market share of Q1 (again, especially in the Western world) is much, much higher than the market share of Q4. There is so much to be gained from these potential donors, but slacktivism allows them to remain on the left side of the matrix.

Given a choice between buying a coffee bag that comes with a contribution to the Global Fund and one that does not, it's obviously better to choose the one that does. But accepting this as the only choice out there to potential donors is a huge misrepresentation of the possibilities of the philanthropic market and the world of social change. Things that mobilize the donors from Q1 to Q2 is where we need to be focusing our energies, not on making t-shirts with charitable donations woven into them.

That is my issue with slacktivism, embedded giving, texting donations, tweeting for charities, whatever you want to call it. People (especially in this country) can and should be doing more to be a part of social change.

(I recognize this was a lot. I appreciate you reading it all the way through. If you have any questions or thoughts on my model, my matrix, my subsequent analysis of it or anything, I'd love to hear from you through email or in the comments.)

Sunday, June 6, 2010

Collective Venture Philanthropy for the Small-Time Donor

Edit: Holden from GiveWell and Lucy from Philanthropy 2173 responded in the comments, and Lucy responded on her blog. Check out what she said and join the discussion. I started a twitter account to better coordinate and respond to the comments. (Sorry I couldn't use vowels.)

I agree with what Holden said that, in practice, this type of site might not be able to promote a lot of necessary due diligence. Both he and Lucy bring up constructive ways to harness the power of social media and use it effectively to help both donors and non-profits. Check out Lucy's response and continue the discussion there or here.

End Edit

I wrote a post a while back criticizing GiveWell--a charity rater that looks at effectiveness--for their own tendency to criticize ineffective charities rather than encourage them to be better. One commentor on that post made the point that GiveWell's strategy is to find the "blue-chip" charities that are a safe bet for small- to medium-level donors, not to help individuals find charities that will be or could be effective. GiveWell reiterated this strategy in a recent post.

In some ways, it makes sense that casual donors should only focus on these sure-bets for effectiveness. It doesn't make sense for the small-beans donor to give to an up-and-coming charity, because if that charity goes under, the money would have been better spent on those "blue-chip" options. In an email to me regarding a previous post, Holden Karnofsky of GiveWell made the point that most start-up non-profits, like most start-up businesses, are funded by professional venture capitalists with lots of money and the "capacity to hold them accountable." People with less money typically don't have the means (or the time) to make sure their contributions are going to good use.

However, in some comments on my previous post on supporting small charities, a few ideas were tossed around about how to get small donors connected to these up-start charities. Mark made the point that now people are more willing to invest in companies before they turn profit, as long as they think they have a good vision (think of Google and many other online start-ups.) This discussion when applied to the non-profit world is the difference between supporting organizations with "high performance"--those charities with a good vision--versus "high impact"--those charities with proven impact, i.e. "blue chip" investments.

Of course, as Karnofsky alluded to, these high performance organizations can completely fail before they obtain their blue-chip status (like the dot com bubble bust.) But I wonder if there is a way for casual donors to be a part of this venture capital stage and still try to maintain some level of accountability.

One viable solution already in place is the prevalence of social media connecting people to charitable means. Many organizations are out there to bring small-time givers together so they can pool their resources and support different charitable projects: DonorsChoose, Kiva, Hope+, and a myriad of corporate-sponsored, Vote For Your Favorite Idea! contests, like the Pepsi Refresh Project. Could this social media technology be harnessed to raise funds for upstart non-profits? (For a cool example of this donor social-media at work, check out this article about some kids who are trying to take down Facebook.)

Accountability will still be an issue with collective venture philanthropy, but several things could be done to try to mitigate the risk: Frequent updates to the donors, a la Kiva, a strict screening process and a focus on best-practices. There will always be risk with venture capital, as many small-time donors have learned from defaulted loans on Kiva. But I know there are many people out there interested in helping something start from the ground up and this site could give people's new ideas a way to get out there and gain support. It would also give non-profits a stronger, broader donor base from the get-go that they can continue to engage as they expand.

Of course, if done poorly, this type of site could end up being a Craig's List of random charity ideas. Things that should have stayed in the dark could be brought to light and fully funded.

Thoughts? Any takers on funding this idea? I'd probably first need a social-media based venture philanthropy site to get it off the ground.

I agree with what Holden said that, in practice, this type of site might not be able to promote a lot of necessary due diligence. Both he and Lucy bring up constructive ways to harness the power of social media and use it effectively to help both donors and non-profits. Check out Lucy's response and continue the discussion there or here.

End Edit

I wrote a post a while back criticizing GiveWell--a charity rater that looks at effectiveness--for their own tendency to criticize ineffective charities rather than encourage them to be better. One commentor on that post made the point that GiveWell's strategy is to find the "blue-chip" charities that are a safe bet for small- to medium-level donors, not to help individuals find charities that will be or could be effective. GiveWell reiterated this strategy in a recent post.

In some ways, it makes sense that casual donors should only focus on these sure-bets for effectiveness. It doesn't make sense for the small-beans donor to give to an up-and-coming charity, because if that charity goes under, the money would have been better spent on those "blue-chip" options. In an email to me regarding a previous post, Holden Karnofsky of GiveWell made the point that most start-up non-profits, like most start-up businesses, are funded by professional venture capitalists with lots of money and the "capacity to hold them accountable." People with less money typically don't have the means (or the time) to make sure their contributions are going to good use.

However, in some comments on my previous post on supporting small charities, a few ideas were tossed around about how to get small donors connected to these up-start charities. Mark made the point that now people are more willing to invest in companies before they turn profit, as long as they think they have a good vision (think of Google and many other online start-ups.) This discussion when applied to the non-profit world is the difference between supporting organizations with "high performance"--those charities with a good vision--versus "high impact"--those charities with proven impact, i.e. "blue chip" investments.

Of course, as Karnofsky alluded to, these high performance organizations can completely fail before they obtain their blue-chip status (like the dot com bubble bust.) But I wonder if there is a way for casual donors to be a part of this venture capital stage and still try to maintain some level of accountability.

One viable solution already in place is the prevalence of social media connecting people to charitable means. Many organizations are out there to bring small-time givers together so they can pool their resources and support different charitable projects: DonorsChoose, Kiva, Hope+, and a myriad of corporate-sponsored, Vote For Your Favorite Idea! contests, like the Pepsi Refresh Project. Could this social media technology be harnessed to raise funds for upstart non-profits? (For a cool example of this donor social-media at work, check out this article about some kids who are trying to take down Facebook.)

Accountability will still be an issue with collective venture philanthropy, but several things could be done to try to mitigate the risk: Frequent updates to the donors, a la Kiva, a strict screening process and a focus on best-practices. There will always be risk with venture capital, as many small-time donors have learned from defaulted loans on Kiva. But I know there are many people out there interested in helping something start from the ground up and this site could give people's new ideas a way to get out there and gain support. It would also give non-profits a stronger, broader donor base from the get-go that they can continue to engage as they expand.

Of course, if done poorly, this type of site could end up being a Craig's List of random charity ideas. Things that should have stayed in the dark could be brought to light and fully funded.

Thoughts? Any takers on funding this idea? I'd probably first need a social-media based venture philanthropy site to get it off the ground.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)